From New Internationalist

May 2005

Planet Earth is home to an astonishing variety of life, from bacteria that live in the extreme heat of volcanic lava to ice-cap dwelling polar bears, from city-based humans to luminous fish in deep ocean trenches. All are interconnected in a fragile web of life called ‘biodiversity’.

Life on earth first evolved in the oceans over 2.5 billion years ago. Perhaps half a million years ago, one species of primate became more and more successful, and humanity spread throughout the world. By 10,000 years ago we were domesticating plants and animals; and by the 20th century our high-energy technologies and productive activities meant we were capable of the total transformation of ecosystems, something unprecedented in history.

Life on earth first evolved in the oceans over 2.5 billion years ago. Perhaps half a million years ago, one species of primate became more and more successful, and humanity spread throughout the world. By 10,000 years ago we were domesticating plants and animals; and by the 20th century our high-energy technologies and productive activities meant we were capable of the total transformation of ecosystems, something unprecedented in history.The number of species threatened with extinction is a clear indicator of the state of the world’s ecosystems. Extinction means the death of birth. Five mass extinctions have happened in the past 500 million years. The sixth and greatest extinction in the history of our planet is happening today. It is almost entirely due to human activity, and is faster than any in history: we are losing species at a rate of up to 1,000 times the natural rate of extinction. Between a third and a half of terrestrial species are expected to die out over the next two centuries if current trends continue unchecked.

Humanity’s threats to biodiversity are manifold, from habitat loss to destruction of grasslands and forests, from overfishing, pollution and contamination to global climate change. The inter-relatedness of ecosystems means that a small loss in one area can affect many other species around it: for example, the decline of the honeybee leaves many fruit crops and flowers unpollinated. For in nature, diversity breeds diversity: trees in turn provide homes and food for birds, insects, other plants and animals and fungi.

This interrelatedness of all beings includes us. Human beings rely directly on the planet’s biodiversity for food, shelter and health; and indirectly for clean water, pure air and fertile soils. The lesson we need to learn urgently is this: we cannot do without the rest of the planet’s biodiversity, but it can do very well without us.

LIFE – THE FACTS

• The Millennium Ecosystems Assessment considered four different scenarios for global development over the next 50 years. In all four, the pressures on ecosystems continue to grow and biodiversity continues to be lost. Between 10% and 15% of plant species may be extinct by 2050.

• Some 23% of mammal species, 12% of bird species and 32% of amphibian species are threatened with extinction.

• Over the past few hundred years, humans have increased the species extinction rate by as much as 1,000 times the background rates typical over the planet’s history.

• In some sea areas the total weight of fish available to be captured is less than a hundredth of that caught before the onset of industrial fishing.

• The distribution of species on Earth is becoming more homogenous. For example, a high proportion of the 100 or so non-native species in the Baltic Sea are native to the North American Great Lakes, while 75% of the 175 recently arrived species in the Great Lakes are native to the Baltic.

Government Spending = Nearly One-Third U.S. Economy

By Bill Ahern

From The Heartland Institute

1999

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, governments in the United States have become increasingly involved in the economy. One indicator of that growing involvement is the ever- higher fraction of the overall economy that is represented by government expenditures.

In 1900, total government expenditures equaled 8.2 percent of GDP. By 1997, that figure had nearly quadrupled, to 31.1 percent. Thanks to currently robust economic growth, it is estimated that by the year 2000 total government expenditures will represent "just" 30.0 percent of GDP.

The composition of government expenditures has also changed dramatically over time. At the turn of the century, most government spending paid for education and training, physical resources, and national defense. Today, most government activity involves transferring income from one group to another. Transfer programs--which represented just 2.0 percent of all government spending in 1900--are expected to account for 42.4 percent of government spending in 1999.

The budgetary authority of the various levels of government has also been transformed over the course of the century. In 1900, the bulk of government spending, 62.2 percent, took place at the state and local levels. Today, the federal government spends more than twice as much as state and local governments combined.

Extreme Weather Extremely Costly

By David Suzuki

From CNEWS

2006

Global warming may have been the last thing on the minds of Vancouverites as they dug out from a record November snowfall and cold snap. But it's another reminder of how much we all depend on the stability of our atmosphere.

While residents of other Canadian cities may scoff at Lotus land's relatively minor misfortunes, the city has certainly had its fair share of weather anomalies lately. First, record rains churned up rivers and caused landslides in the city's watersheds, leading to turbidity problems in the drinking water supply and a boil-water advisory across the region. Then, just as the water began to clear, a record cold and snowfall paralyzed the city.

What has this got to do with global warming? Well, extreme weather events like these are exactly the kind of thing climatologists say will become more common as our climate heats up. How confusing is that? Global warming can cause heavy snowfalls. But it's true.

This ability to link global warming to so many weather-related phenomena has created a bit of a joke: Blame everything on global warming. Stock market down? Global warming. Can't get a date? Global warming.

But underlying the joke is a serious fact. Our atmosphere is connected to everything - including us. By adding vast amounts of heat-trapping gases like carbon dioxide to the atmosphere (from our industries, cars and power plants) we're trapping more heat near the surface of the earth. More heat means more energy. Adding so much energy to our atmosphere creates the potential for more violent outbursts - like the weather Vancouver has been feeling lately.

This is why it's so imperative and urgent for humanity to get this problem under control. It's not as though global warming is just a minor inconvenience. Left unchecked, it's set to become a major hindrance to economic growth and international development. Vancouver newspapers were full of stories during both extreme weather events about how much these "natural" disasters were going to cost the city's economy.

In developing countries, severe weather events are doing more than harming the economy - they're killing people. Of course, extreme weather has always killed people. But in a recent article in the journal Science, Indian researchers report that extreme summer monsoon rains in India are becoming more common. Last summer, for example, more than 1,000 people died during one torrential rainstorm around Mumbai.

For the Science study, researchers analyzed data during the period 1951 to 2000 from more than 1,800 weather stations around central and eastern India. They found that while overall rainfall remained fairly consistent during the 50-year period, the number of extreme rainfall events doubled. Researchers cannot conclusively say that human-induced global warming is the cause, but the study's findings are in line with what computer models predict will continue to happen unless we seriously curb greenhouse gas emissions.

The new research helps shed light on why, when global warming models predict more rain in places like India, rainfall there doesn't seem to have increased overall. The answer is that, although annual average rainfall hasn't necessarily increased, extreme rainfalls have. That's unfortunate because more steady rainfall could actually benefit India's agriculture. Extreme weather benefits no one, especially in a developing country like India that lacks the infrastructure to deal with it.

Keep that in mind for Canada. Canadians by and large sure wouldn't mind more pleasant weather. But global warming won't benefit anyone if more extreme weather is the result. Just ask folks in Vancouver.

Take the Nature Challenge and learn more at www.davidsuzuki.org.

The Star in Man : Jung and Technology

By Dolores E. Brien

From The Jung Page

2005

Jung's references to technology are few and pessimistic. Technology itself is neutral, he wrote, neither good nor bad. Whether it does harm to us, or not, depends on our attitude towards it, how we use it. But human nature being what it is, it is certain we will use it for evil as well as good. He thought that technology gendered an "imbalance" in life, dulling our "natural versatility of action" and dulling our instincts.

Technology has given us an illusion that we are superior to nature and that we can do whatever we will to do. Unless we strip ourselves of our false sense of power, nature, both that within us and without, will one day destroy us. We must ask ourselves: "Who is applying this technical skill? In whose hands does this power lie? "Our technical capabilities have become so dangerous that we must question what kind of people are they who control them. How, we need to ask, can the the mind of modern Western man be changed "so that he would renounce his terrible skill".

According to Jung, we project onto technology what in earlier eras we would have projected onto the supernatural. For many, indeed, technology is experienced as numinous. Under the influence of science along with technology, we are less willing to attribute events to divine intervention. But unconsciously, we still cling to the hope of a revelation of that archetype of "order, deliverance, salvation and wholeness." We express this hope, however, in symbols derived from technology rather than from traditional religious beliefs or from mythology.

It is characteristic of our time that the archetype, in contrast to its previous manifestations, should now take the form of an object, a technological construction, in order to avoid the odiousness of mythological personification. Anything that looks technological goes down without difficulty with modern man. The possibility of space travel has made the unpopular idea of metaphysical intervention much more acceptable.

(As an apt if bizarre case in point, readers will remember the account of the Heaven's Gate cult of but a few years ago. The members of the cult members committed suicide in the belief that after death they would be re-united in a space-ship waiting for them in outerspace.)

A more ambiguous, but highly evocative association with technology came to Jung in the form of a youthful fantasy. In later years, he was able to recall it vividly, as he did in a letter to Aniela Jaffé. Aniela Jaffé had written to Jung about her dream of a copper pot which had been hung from a ceiling. Electrical wires which came from all directions made it vibrate but eventually the wires disappeared and the pot vibrated from "atmospheric electric oscillations." Jung found the dream was remarkably similar to what he referred to as "my first systematic fantasy" (at the age of about 15 or 16) which for weeks occupied him while on his long and boring walk to school. Some fifteen years later in Memories, Dreams, Reflections Jung related the daydream again, but in greater detail. He was, he remembered, king of an island in a great lake. On the island was a mountain with a small, medieval town at the bottom. He lived on the top of the mountain in a watchtower which was fortified with weapons and heavy cannon. In it there was a fine library "where you could find everything worth knowing." Below in the town there lived a few hundred inhabitants. Although there was a mayor and a council of elders, he held the post of justice of the peace and advisor but held court only occasionally.

The ego-centered imagery of this young "master of the universe," ruling wisely but alone from his mountain top tower, conveys a sense of order, rationality and benign power. His island is well defended against enemies, the affairs of his citizens are kept well in hand by his delegates. Everything is nicely under control leaving him free to explore the treasures of the library. But in the heart of his tower, this young ruler discovered a strange secret, which came to him, Jung tells us, as a shock.

The tower harbored a hidden "nerve center" which Jung first describes as a thick cable of twisted copper wire serving as a conduit for a flow of energy taken from the air. Initially its form reminds him of a tree with its branches resembling a sort of crown. But then he changes his mind and says, no, it is more like an inverted tree with its roots thrust into the air. Although Jung does not say so directly, the cable is an image of "the world-tree" reaching from heaven to earth, found in many mythologies and prominently in alchemy. Jung calls the cable vaguely and somewhat ominously, an "inconceivable something." An unknown, "mysterious substance," drawn from the air, is sucked down to the cellar and into a laboratory where he transforms it into gold, specifically gold coins. "This was really an arcanum" he remembered, "of whose nature I neither had nor wished to form any conception."

Jung recalled that he consciously refrained from figuring out how this transformation took place. It was as if "there was a kind of inner prohibition: one was not supposed to look into it too closely, nor ask what kind of substance was extracted from the air." He felt at the time that a very important secret of nature had been given to him and one which he had to keep not only from the council of elders, but also from himself.

Jung responded to Jaffé that her dream of an electrical circuit was an important symbol of the self. He must have had in mind his own fantasy as well. "Through the self," he wrote to her, 'we are plunged into the torrent of cosmic events. Everything essential happens in the self and the ego functions as a receiver, spectator, and transmitter. What is so peculiar is the symbolization of the self as an apparatus. A 'machine' is always something thought up, deliberately put together for a definite purpose. Who has invented this machine? (Cf. the symbol of the 'world clock!') The Tantrists say that things represent the distinctness of God's thoughts. The machine is a microcosm, what Paracelsus called 'the star in man.' I always have the feeling that these symbols touch on the great secrets, the magnalia Dei.'

This daydream of the fifteen-year-old Jung foreshadows the adult Jung's fascination with alchemy. We know from Memories Dreams, Reflections that the imaginings of his youth carried profound meaning for him that influenced him throughout his lifetime. But what more can we draw from this brief passage? His remarks to Jaffé very likely had a source in two of Jung's studies he had been recently working on. His lectures on Paracelsus were published in 1942, the same year as his reply to Jaffé. Earlier in 1938 he had published his commentary on "The Visions of Zosimos,"an important third century alchemist. The imagery of the fantasy-the copper cable, the world-tree, the transformation into gold-can be found in both studies along with Jung's interpretation of their symbolic meaning. It is reasonable to presume that when he wrote to Jaffé he was still very much immersed in their revelations. What intrigues Jung is something new-the association of the self with technological apparatus.

The self as tool, as machine

When Jung speaks of the self functioning as "receiver, spectator, and transmitter," he is imagining it as a kind of instrument. That which exists outside the self-a thing-is received by the self, is observed by it, and is communicated further by that self. The self acts as a funnel for the psychic energy which is contained in the object. Here the role of the self seems passive, serving as a "spectator," somewhat analogous to a camera or television. What is communicated in turn to the cosmos, however, bears the imprint of the self through which it has been conducted. But the self is more than passive receptor mirroring, or imaging what it has received.

In the fantasy, the flow of energy ends in a laboratory hidden in the cellar. Jung refers to the laboratory itself as an elaborate machine. How strange, Jung writes to Jaffé, that the self should be symbolized in this way-as a "machine," an "apparatus," in a word, as a piece of technology. After all, a tool is something made by us, and for our purpose. The self it seems is not only a receptor, but an agent as well, or in alchemical terms, the artifex. It is the "self" who achieves the transformation of the energy into gold. Jung's wonder at this mysterious apparatus, reminds him of Paracelsus's idea concerning the "star in man" and therein he finds a possible explanation of its meaning.

The star in man

In keeping with the traditional alchemist notion of the macro-microcosm, Paracelsus believed that the human being is a small cosmos, and that what governs the great cosmos is identical with what governs the little cosmos of man.

[Man] can be understood only as an image of the macrocosm, of the Great Creature. Only then does it become manifest what is in him. For what is outside is also inside; and what is not outside man is not inside. The outer and the inner are one thing, one constellation, one influence, one concordance, one duration, one fruit.

{Man} carries the stars within himself, . . . he is the microcosm, and thus carries in him the whole firmament with all its influences.

There is nothing in heaven or in earth that is not also in man. . . .In him is God who is also in Heaven; and all the forces of Heaven operate likewise in man. Where else can Heaven be rediscovered if not in man? Since it acts from us, it must also be in us.

That which Paracelsus called the "Light of Nature," the "star in man" is also known as the filius philosophorum. In commenting on Paracelsus and the "star in man," Jung notes that this "natural light of man," this "filius philosophorum" "was extracted from matter by human art and, by means of the opus made into a new-light bringer." In the case of Christ's incarnation, the miracle of man's salvation is accomplished by God; in the latter, the salvation or transfiguration of the universe is brought about by the mind of man. Man, as it were, "takes the place of the Creator." In judging the outcome of this notion of the alchemists, Jung recognizes its contribution to the inevitable dominance of science and technology.

Medieval alchemy prepared the way for the greatest intervention in the divine world order that man has ever attempted: alchemy was the dawn of the scientific age, when the daemon of the scientific spirit compelled the forces of nature to serve man to an extent that had never been known before. It was from the spirit of alchemy that Goethe wrought the figure of the "superman" Faust, and this superman led Nietszsche's Zarathrustra to declare that God was dead and to proclaim the will to give birth to the superman, to "create a god for yourself out of your seven devils." Here we find the true roots, the preparatory processes deep in the psyche, which unleased the forces at work in the world today. Science and technology have indeed conquered the world, but whether the psyche has gained anything is another matter.

This statement is consistent with Jung's opinion, mentioned earlier, about the danger of technology as the result of the manipulation of nature. The alchemists made a distinction between God who became Man in Christ, the light of the world and the filius philosophorum, "the light of nature,"who was "extracted from matter by human art and, by means of the opus, made into a new light-bringer." In the case of the former man's situation is "I under God." With the other, it is "God under me." Jung excuses the alchemists as being naive and not aware of what they were doing. Nevertheless the splitting off of divine from human power had been irrevocably accomplished. From now on, human beings will think and act if they were God. Nature is subordinated too, becoming primarily a tool to fulfill our needs and desires.

In an excursus on alchemy in The Soul's Logical Life, Wolfgang Giegerich adds to Jung's insight into the profound and permanent transition initiated by the alchemists in humankind's relation to both nature and the divine. The ancient power of myth, Giegerich states, in which knowledge is reserved to the Gods alone is subverted with the advent of alchemy. No longer is knowledge something which is received, but rather as something to be acquired through experiment and invention. Under the sway of the Gods, man can only attempt to decipher that which has been given to him. The alchemist, on the other hand, "acts on his own resonsibility." "He is no longer in the status of passive recipient, as man had been on the mythological stage of the soul's development." From this change in man's attitude towards God and nature, science and technology evolve.

What is inside is outside and what is outside is inside

It is significant, that in his letter to Jaffé Jung makes no judgment about the meaning of the fantasy and does not try to draw any conclusions from it. Instead he leaves open what this "star in man," might mean. What does it signify that we are "plunged into the torrent of cosmic events?" Echoing Paracelsus, he had said elsewhere that there is nothing outside, which is not also inside. Or conversely, nothing inside which is not outside. He writes wonderingly that he "always has the feeling that these symbols touch on the great secrets, the magnalia Dei."

Jung thought of the machine as a symbol of the self. This machine, in Jung's fantasy, transforms energy into gold. In his commentaries on Zosimos, Jung had observed: "It is in truth the inner man. . . who passes through the stages that transform the copper into silver and the silver into gold, and who thus undergoes a gradual enhancement of value." He admitted that the modern individual would find it very odd that metals could be symbols for spiritual growth. But he claimed this was an old tradition and was not unique to the alchemists. He cites a dream of Zarathustra in which he saw a tree with branches of gold, silver, steel and mixed iron. This tree, according to Jung, "corresponds to the metallic tree of alchemy, the arbor philosphica, which, if it has any meaning at all, symbolizes spiritual growth and the highest illumination." This is the same as the "world-tree" which his copper cable resembled (CW 13, para. 288). What is strange, of course, is that metal appears cold and without life and therefore the opposite of spirit. But if the spirit itself seems leaden perhaps one ought to seek that metal out because there may be hidden in it "either a deadly demon or the dove of the Holy Ghost."

In that same passage referring to the arbor philosophica, Jung wonders if the greed for precious metals was not nature's way "to prod man's consciousness towards greater expansion and greater clarity." (CW 13, paras. 118, 119). This is an unexpected remark especially given Jung's usual pessimistic attitude towards human intentions and behavior. It is reminiscent of Wolfgang Giegerich's controversial assertion that the magnum opus of our time is the "bottom line," the making of money. If we concede (many do not) that this is indeed the magnum opus of our time, we are still inclined to see it as more as an evil than as a good, despite the good that money also can do. The magnum opus was never sought in moral terms of good and evil. This question that Jung throws in somewhat offhandedly, is worth pondering. One may not want to honor human greed for money symbolized by "precious metals" as the magnum opus, but few can doubt that it is an overwhelmingly dominant force in our market driven, global culture. Is it possible to imagine that in the relentless pursuit of profit we will come to "a greater expansion and greater clarity?" Towards what and of what? we may well ask.

Technology tends to be split off from us; it exists "out there, " useful to us, but separate and distinct from us. It is surely not us, we believe. We depend on it, it is true. Life, despite the protestations of the modern day Luddites, would be inconceivable without it. At the same time we are suspicious and fearful of its seemingly autonomous, self-generating power. Jung returned repeatedly to Paracelsus's refrain, that what is inside is also outside but conversely what is outside is also inside. Are technology, as the art of making, crafting (in the original meaning of the word techne) and the end product of that making , in fact, external to us?

Are they purely instrumental and merely subject to our purposes or intentions? Could it be that technology, this "machine," this "apparatus" is more than a symbol of the self, but actually partakes of the self in some integral way, could be a certain manifestation of the self? "Who,"asked Jung, "has invented this machine?" After all, this machine has been "thought up" and created by man. It was "inside" him in some sense before it was produced, that is, also found on the "outside." This suggests that there may well be a more intimate relationship between the individual and technology than has been so far acknowledged.

Jung's thinking on technology is not explicit nor developed, but, as is so often the case with Jung, seminal, richly evocative. Alchemy is arcane, but technology today is just as arcane even to the adepts of technology, never mind the rest of us. With Jung, not as a guide exactly, but as a kind of prod, the "star in man" of the former may cast its light on the latter.

Challenging Impunity

The International Criminal Court was launched in April 2002. Noah Novogrodsky outlines the goals of the Court and describes the barriers to its success.

From New Internationalist

In mid-October this year the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued indictments for the arrest of Joseph Kony and four other leaders of Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The LRA is notorious for a 21-year campaign of terror in Northern Uganda – including the abduction of thousands of children and the widespread use of child soldiers. Kony and the other LRA leaders are charged with ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘war crimes’.

The case against the LRA is a test of the power and limits of the ICC just three years after its birth. The new legal body taking shape at The Hague is a direct legacy of the Nuremberg tribunals which tried Nazi war criminals after World War Two. But unlike Nuremberg the ICC contains the promise of a universal court for universal crimes.

It is this elusive goal that sustains the victims of human rights abuses hungry for individual accountability, the diplomats who negotiated the Court’s creation in Rome during the summer of 1998, and the international lawyers and activists who desperately want such an institution.

Supporters of the Court believe it is the most significant advance in international human rights law in the last half-century. In addition to Northern Uganda, the ICC has begun investigations into atrocities in the Congo and, most recently, in Darfur, Sudan. The Chief Prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, is an Argentinean with a domestic record of successful prosecutions of corrupt politicians, organized criminals and the generals responsible for mass ‘disappearances’ during Argentina’s ‘dirty war’ of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Naming war criminals

But what can the Court really do? The ICC has no police force connected to its operations, so it can’t directly arrest indicted suspects. If the prosecutor can persuade UN peacekeepers or sympathetic states to arrest suspects, the Court will provide criminal justice for a select number of the world’s worst killers. In the process the ICC hopes to destigmatize warring communities and rid them of collective guilt by assigning blame to individuals.

For victims and their families the Court offers the possibility of retribution through law – a forum where they can bear witness to the atrocities they’ve experienced – and a compensation fund. Equally important, the ICC aims to influence international politics by naming and isolating war criminals. In 1999 Louise Arbour, former UN war crimes prosecutor for the Balkans, timed the indictment of Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic to ensure that NATO would not cut a deal over Kosovo with a criminal suspect. Two years later, Milosevic was arrested by Serbian police and turned over to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

Even without its enforcement problems, the Court will have to overcome external enemies and internal deficiencies. The fact that the ICC’s first cases are all in Africa has led to the predictable charge that the Court represents the selective imposition of Western values on poor states.

The Court is an international anomaly – an institution created by treaty among 99 states that functions without the co-operation of a few key actors, many of whom are openly hostile to it. That treaty – the 1998 Rome Statute – is the product of compromise. In the end, the Treaty created a court capable of prosecuting only three universal offences: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.

The result is a codification of international criminal norms which will stop the creation of ad hoc UN criminal tribunals – like the ones for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The Court’s statute identifies rape and torture as crimes against humanity and provides clear definitions of liability for officers in command positions who are barred from arguing that they were simply ‘following orders’. The statute also guarantees defendants substantial ‘due process’ protections (for the accused) and preserves a right of appeal. Despotic heads of state from signatory states are stripped of the immunity that allowed Idi Amin, Uganda’s one-time dictator, to retire in luxury. The Court also entrenches the principle of ‘complementarity’ – which means the ICC will step aside if legitimate national courts decide to try war criminals.

The ICC has the power to investigate human rights abuses on the territory of states that have signed and ratified the treaty or when the suspect hails from a signatory state. If the Security Council refers a matter to the Court, as it did belatedly in response to the slaughter in Darfur, the ICC may take jurisdiction even where the affected state objects to the presence of outside investigators. But more often cases will come from a state that is unable or unwilling to prosecute serious crimes committed on its own soil. In Uganda, for example, the Government is all too willing to let the ICC prosecute the LRA. (If the Court were to indict Government soldiers for their abuses, the picture might look very different). Any mass crime, committed in a signatory state unable to mount a genuine prosecution, can come before the ICC.

Of course, the Court only binds those states (and, by extension, individuals from those states) that sign and ratify the treaty. In theory, however, the Court could exercise jurisdiction over an individual from a non-state party who commits grave violations on the territory of a signatory state. Peacekeepers or foreign forces from non-state parties are potentially bound to the Court if they are arrested for crimes committed on the soil of a signatory state.

Bilateral deals

This is the source of the United States’ well-publicized opposition to the Court. Notwithstanding a litany of safeguards – among them the ICC’s limited jurisdiction to try only the most egregious international crimes, the Court’s inability to try crimes committed on US soil and its explicit deference to domestic procedures – the Bush Administration so loathes the ICC that it attempted to ‘unsign’ the treaty. (President Clinton actually signed the treaty on 31 December 2000 but refused to submit it to the Senate for ratification.)

Washington has not only refused to join the Court, it has actively lobbied against it. In response to concerns that the Court would try US soldiers or officials in frivolous or politically motivated cases, the Bush Administration has negotiated bilateral deals with dozens of countries who’ve agreed never to surrender US citizens to the Court, regardless of the alleged crimes or the site of the offence. Congress also passed the ‘American Servicemembers’ Protection Act’ which prevents the US from aiding the Court. The bill was nicknamed ‘the Hague Invasion Act’ – the ICC is based in the Netherlands and the act pre-authorizes the President to use force to free American soldiers or their colleagues if they were ever brought before the Court.

External opposition is not the Court’s only problem. The limited scope of the ICC’s statute precludes it from seizing jurisdiction over many high-profile international crimes. For example, although the ICC was created by the UN, attacks on UN personnel may only be considered if committed during an armed conflict on the territory of a member state. When the UN’s headquarters in Baghdad was blown up in the summer of 2003, ICC investigators were powerless to probe the incident.

The Court’s focus on consensus definitions of war crimes and genocide limits its range of potential cases and leaves it, quite literally, fighting the last war. The ICC thus reflects the tragedy of Bosnia in 1993, not Afghanistan in 2005. Post 9/11, suspected non-state terrorists are detained by US forces in legal limbo at Guantánamo Bay. And human smugglers operate unchecked in states with underdeveloped legal systems, instead of being sent to the ICC.

Finally, the ICC faces the very real problem that it is powerless to address abuses arising from many of the world’s great powers. Russia, China, Iraq, India, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia have joined the US in refusing to sign the Rome Treaty. Much of this is due to domestic concerns – Iran has no interest in allowing an international body to examine the horrors of Iranian prisons. But the cost to the international community is significant. China and India are burgeoning economic and geopolitical powers; their absence from a court capable of trying individuals according to common standards erodes the notion of universal justice. At present, sex traffickers, arms dealers, even international terrorists, from countries that have not signed the Rome Statute, are beyond the Court’s reach.

The ICC is left to prosecute ‘crimes against humanity’, ‘genocide’ and ‘war crimes’ in states that have joined the Court. In addition to Uganda, the list of signatories where such crimes may have been committed since 1 July 2002 includes the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Colombia and Sierra Leone. Civil wars may explain why each of those states has joined – they are undoubtedly hoping the Court will prosecute rebel forces – but the legal hook remains. Sadly, there is little current evidence that the spectre of ICC prosecutions has changed the behaviour of human rights abusers on the ground. In Northern Uganda many human rights advocates fear that the ICC will complicate efforts to achieve a negotiated settlement after decades of fighting.

The challenge will be to conduct fair and transparent trials in the face of criticism that the Court is merely a vehicle for Northern states to condemn select crimes in the South – not an instrument of universal justice. Over time the states that have joined the ICC hope to persuade the others. The goal is to lead by example, prosecuting humanity’s worst crimes effectively and reversing the past century’s culture of impunity.

Continued US opposition hurts but, as the Uganda indictments demonstrate, the Bush Administration has been unable to derail the ICC. Likewise, a change in the US position will not guarantee the Court’s future success. For that, its fortunes may well turn on an expansion in the list of crimes within its authority and the involvement of emerging powers as members.

Imagine this: an institution that includes China and India – and can prosecute Joseph Kony as well as Private Lynndie England of Abu Ghraib infamy. That will truly be an International Criminal Court.

The ICC has just targeted Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army for crimes against humanity, including the abduction of children as armed fighters. These former child soldiers are now at a rehabilitation centre in neighbouring Sierra Leone. Photo: Clive Shirley / Globalaware

Noah Benjamin Novogrodsky is Director of the International Human Rights Program and Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Toronto

Time's "Green Century" Advice: Less Environmental Activism

From Extra!

2002

Time's August 26 cover feature on "The Green Century" promises to explain "How to Save the Earth." The answer, according to a prominent article inside: blame environmentalists for a lack of environmental progress.

Andrew Goldstein's "Too Green for Their Own Good?" begins with this question: "How come, at a time when the environmental movement is stronger and richer than ever, our most pressing ecological problems just get worse?" One answer might be that the strength of the environmental movement is a testament to the public’s concern for the declining state of the environment. But for Goldstein, it seems to be almost the opposite: Environmentalists are partly to blame, since "it's easier to protest, to hurl venom at practices you don't like, than to find new ways to do business and create change." He writes that the "dogma of traditional green activism" might be what's wrong, as it "has done little to save the planet."

Goldstein offers plenty of advice for green groups-- like "Embrace the Market" and "Business Is Not the Enemy"-- while presenting remarkably little evidence to back up his opinions. "For starters," he writes, "when companies make efforts to turn green, environmentalists shouldn't jump down their throats the minute they see any backsliding." As an example, a former Greenpeace executive turned corporate consultant criticizes environmental groups for opposing Ford Motor Co., "arguably Detroit's most environmentally friendly carmaker," during the debate over fuel-efficiency standards. But as Goldstein parenthetically notes, Ford was lobbying against raising those standards, which have not been increased since 1985. Is it really "dogma" to think that 17 years later, standards should be raised?

It's true that Ford has made a special PR effort to enhance its green reputation. One tactic: sponsoring another major Time magazine environmental series, "Heroes for the Planet." The magazine was very upfront about how Ford's sponsorship would influence its reporting: Time's international editor explained that the series would be unlikely to address auto pollution, since "we don't run airline ads next to stories about airline crashes" (Wall Street Journal, 9/21/98). Ford has two full-page ads in the August 26 issue.

Goldstein also chastises environmental groups for not supporting a Clinton-era emissions trading proposal to reduce emissions by allowing power plants to trade "pollution credits" with other companies. Environmentalists blocked the plan, he says, because they viewed it as a ruse for companies to avoid cutting back on emissions. The result of such opposition was clear to Time: "Result: Today the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has no ability to regulate carbon, and the old, pollution-spewing plants are still in operation."

Contrary to Goldstein's assertions, some major environmental groups, like the Environmental Defense Fund, did in fact endorse emissions-trading plans in the 1990s; such a plan was enacted to limit acid rain in 1990 and expanded in 1995. While some green groups are skeptical that such plans are the most effective way to reduce pollution, the most important opponents to the Clinton proposal were global-warming skeptics in Congress (New York Times, 11/12/00).

More importantly, Goldstein neglects a more direct interference with the EPA: the Bush administration's well-publicized decision in March 2001 to remove carbon dioxide from the list of power plant emissions that the Environmental Protection Agency would regulate. This decision was linked to the concerns of energy companies, not pressure from environmentalists (Associated Press, 4/26/02).

Goldstein has similar advice on the fight over genetically modified foods, advising environmentalists that "it's time to raise the white flag and ask the world's bioengineers for a seat at the bargaining table." Suggesting that biotechnology is the key to ending hunger, he explains, "What could be better for the environment than a cheap, simple way for farmers to double or triple their output while using fewer pesticides on less land?" That sounds nice, but the notion that biotech dramatically improves yields while lowering pesticide use is nothing if not disputed. For instance, some studies have shown that farmers planting bioengineered crops like Monsanto's Roundup Ready soy use as much as five time more herbicide than farmers using conventional crops (Rachel's Environment & Health News, 2/15/01). Studies of crop yields show marginal increases in production, which in some cases do not make up for the increased costs of the genetically modified seeds (USDA Economic Research Service, 5/16/02).

Even if one accepts, for the sake of argument, that biotech is unambiguously good at increasing farm production, would that really feed the hungry? The anti-hunger group Food First has calculated that the world's farmers already produce enough to provide every person 4.3 pounds of food per day, if only it were distributed equitably (www.foodfirst.org). Rather than address such analysis directly, however, Goldstein dismisses critics of biotechnology as "crop tramplers and lab burners."

The magazine closes by recommending that green groups and "an environmentally friendly media" should stop using "scare tactics" and rely instead on sound science and honest analysis. Goldstein's use of vague, misleading anecdotes to bash environmentalists isn't particularly helpful to the environment-- but it is friendly to the corporate advertisers, including auto makers and oil companies, who sponsored Time's "How to Save the Earth" issue.

ACTION: Encourage Time to hold its reporting on environmental activism to a higher standard. "Too Green for Their Own Good?" relies on weak anecdotal arguments to bash environmentalists, while ignoring or downplaying evidence that would challenge the article's thesis. Ask Time whether corporate sponsorship of its environmental coverage influenced its journalism, as it did in 1998.

PRISONS ARE A FAILED EXPERIMENT (ESPECIALLY FOR WOMEN)(excerpt)

FromPrisonJustice.ca

The Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies and the Native Women's Association of Canada made the original complaint to the Commission on behalf of women who were being held in Saskatchewan Maximum Security Penitentiary for Men.

This complaint is also supported by the Aboriginal Women's Action Network, Assembly of First Nations, National Association of Friendship Centres, Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations, Strength in Sisterhood, Disabled Women's Network Canada, National Action Committee on the Status of Women, Canadian Bar Association and Amnesty International.

It alleges that the Canadian government has breached its fiduciary duties to federally sentenced women in Canada and has disregarded the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and certain international human rights obligations, including the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners, which, in 1975, Canada agreed to uphold. Information on the full submissions made to the Canadian Human Rights Commission can be viewed on line at http://www.elizabethfry.ca Women in Prison

“Most importantly, the risks that they [women] pose to the public, as a group, is minimal, and at that, considerably different from the security risk posed by men” (Arbour, 1996: 228). Women represent a small portion of Canada's prison population and their particular needs are overlooked, especially in the areas of meaningful treatment and life-skills programs. Women's crimes are predominantly non-violent and reflect the social and economic standing of women in society. 75 per cent of women serving time do so for minor offences such as shoplifting, fraud, or drug and alcohol offences. The needs of women in prison reflect the same needs of as those in the community at large. 35 per cent of provincially and 48 per cent of federally sentenced women have a grade nine education or lower, and 40 per cent have been classified as illiterate.

Most of the women serving time were unemployed at the time of their arrest. Consider first that 70 per cent of the world's poor are women, and that single mothers with children under the age of 18 have a poverty rate of 57 per cent: Two-thirds of federally sentenced women are single mothers, many of whom lose their children to social services and must contend with regaining custody upon their release. Seventy-two per cent of provincially and 82 per cent of federally sentenced women have histories of physical and/or sexual abuse. In terms of violent offences committed by women, 62 per cent of these charges are for ‘low-level’ or ‘common’ assault. Most women serving time for violent offences committed their crime against a spouse or partner, and they are likely to report having been physically or sexually abused, often by the person they assaulted. There are only 64 women serving life sentences for murder in Canada.

Discriminatory Correctional Laws and Policies

Correctional laws and policies discriminate against all women. Of particular concern is the over-classification of federally sentenced women as ‘maximum security.’ Approximately 42 per cent of federally sentenced women are classified as minimum security, yet are imprisoned in facilities that provide much higher security than most of them require. Federally sentenced women do not have the same access as men to lower security institutions and halfway houses, programming, education, or family contact.

Other examples of discrimination are the utter lack of adequate programs and services for federally sentenced women at all security levels; women-centred programs, programs for addiction and health, education and employment training such as vocational training, computer maintenance and upgrading education and programs linked to upgrading in the community.

Of particular concern for women in prison is the lack of healthcare services. Women in prison have as much need for specialized care (e.g. gynaecology and maternity that are specific to women) as do women outside of prison. Additional considerations for the proper medical care of women versus men includes dental care services such as prenatal and postnatal care in particular.

Further, treatment services focused on overcoming histories of drug and/or alcohol dependency, as reasons for dependencies are different for women than for men. Psychological, psychiatric and counselling services for overcoming difficulties including but not limited to abuse issues, which should be provided by women healthcare professionals. Finally, because women more often than men are responsible for the care taking needs of their parents and elders, parenting services such as childcare and elder care are also needed.

Since the year 2000 closing the Prison for Women (P4W) in Kingston, Ontario, maximum-security women have been transferred en masse to isolated sections of men's prisons. As a result, there has been a dramatic increase in suicide attempts and other self-destructive acts. As one female prisoner explains: “women try to find a way out of these inhumane conditions, even through death.”

Canada is in the process of ignoring every recommendation made on the treatment of women in prison and is in the process of building five new ‘super’ maximum-security prisons for women. Other concerns for imprisoned women are the virtual absence of minimum-security conditions for women, the labelling of women with mental health problems as dangerous, and the continued use of male guards on the front lines of women's prisons.

More recently, in 2003, women formerly housed in men’s prisons are being transferred into the newly constructed, special maximum security ‘pods’ located in each regional prison for federally sentenced women despite the fact that much research (i.e. the Correctional Services of Canada’s 1992 Regional Facilities for Federally Sentenced Women Operation Plan) indicates that federally sentenced women are not generally a danger to others and do not require maximum-security accommodation. Rather, this research shows that less than five percent of the women warranted a maximum-security classification while the large majority being either minimum or low medium.

These special maximum-security ‘pods’ mean that women must endure more egregious conditions. For example, in the men’s prisons, these women were held to conditions governing federally sentenced men, albeit with considerably fewer programs, movement and benefits. However, after their transfer out of the men’s prisons, these women, while wanting to be closer to families, communities and ‘sister’ prisoners must contend with poorer quality and quantity of recreation and food while suffering more extreme custodial sanctions in facilities for federally sentence women.

One formerly federally sentenced woman comments on the special maximum-security ‘pods’

Imagine your reactions if you were just one Aboriginal woman, incarcerated since 1978 when - after suffering these assaults by uniformed men, in 1994 you are transferred to a men’s penitentiary in Saskatchewan. Termed “therapy.” You manage to ‘survive’ another more than eight years under segregated conditions until transferred in March, 2003 to one of the “new” maximum security units for women.

Here you are denied all rehabilitation-relevant programs including your own rights under s.15 of the 1985 Charter enactment and the 1992 CCRA, which includes the right to full participation in all Aboriginal spirituality. You must complete the mandatory correctional “programming;” you must agree to be handcuffed and shackled and while accompanied by two officers, be degraded and be used to instil fear and from that fear - compliance throughout the rest of the population - all in order to gain a few hours in the gym while the other women are barred from the same gym and locked down during this movement! You are expected to show respect to your keepers throughout this ordeal.

Female Aboriginal Prisoners

Aboriginal peoples are over-represented in Canadian prisons. In 1999, the incarceration rate for Aboriginal people was 735 per 100,000 of the Canadian population, compared to a national average incarceration rate of 151 per 100,000. “Discrimination against Aboriginal women is rampant in Canada's federal prisons”, says the Native Women's Association of Canada (NWAC). Aboriginal women represent 27 per cent of all women serving federal time, yet account for less than two per cent of Canada's population. Moreover, 50 per cent of women classified as ‘maximum security’ prisoners are Aboriginal women.

Aboriginal women in prison often go into federal facilities on lesser charges, and commit infractions in prison that lead to longer sentences. Those federally sentenced women classified as ‘maximum security’ have no access to core programs and services designed for women under federal law, and are denied specific programs designed for Aboriginal prisoners. Many of these female Aboriginal prisoners have been serving time involuntarily in men’s prisons and psychiatric wards. Serving time in a men’s prison not only puts these women at risk to male violence, but also denies them equal access to the programs and services that the men receive.

Kim Pate, the Executive Director of the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, draws attention to the fact that Aboriginal women and women with disabilities are particularly discriminated against: “Being Aboriginal means you are seen as higher risk; being poor means you are seen as higher risk; and being disabled means you are seen as higher risk. All of this results in women receiving a higher security classification, so if you are a poor, Aboriginal woman with a disability, they literally throw away the key.”

Women Prisoners with Mental and Developmental Disabilities

The Disabled Women's Network Canada states that federally sentenced women with mental and developmental disabilities are being discriminated against under Section 17 of the Corrections and Conditional Release Regulation, which equates mental disability with a security risk. This legislation applies higher security classifications to these women, and perpetuates negative stereotypes and assumptions, which characterise mental disability as dangerous. Because of their higher security classifications based on disability, women who are suicidal or have mental or cognitive disabilities, are often isolated, deprived of clothing, and placed in stripped or barren cells.

Prisons have become a substitute for community-based mental health services. With the increased cutbacks to healthcare and social programs, the law is increasingly coming into conflict with women's lives, as they are relegated into prisons instead of receiving appropriate services within the community.

Canada Sacks Three Whistle-Blowing Scientists

From healthcoalition.ca

The Canadian government fired three high-profile scientists to punish them for publicly challenging federal decisions on veterinary drugs, the scientists' union said on Thursday.

But a spokesman for Health Canada said the dismissal of Margaret Haydon, Shiv Chopra and Gerard Lambert had nothing to do with their whistle-blowing activities. "There is absolutely no connection," said Ryan Baker, a spokesman for the department, where the scientists worked in a section that reviews and approves veterinary drugs. "This is not because of anything they may have said publicly," Baker said.

The scientists have a lengthy history of disagreement with the department, which has reprimanded them in the past. Haydon and Chopra spoke out against a growth hormone for dairy cattle, called bovine somatotropin, that Monsanto Co. unsuccessfully applied to sell in Canada in the 1990s. They said the company did not submit enough information to prove the drug was safe for cows or humans, and complained they were pressured by the department to approve it.

More recently, Chopra and Lambert complained the department approved a new method of use for the antibiotic tylosin, marketed by the Canadian animal health division of Eli Lilly and Co., despite their concerns that it could lead to antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Haydon also criticized livestock feed rules in the wake of Canada's first homegrown case of mad cow disease last year. The precise reasons for the firings were outlined in letters delivered to the scientists at their homes on Wednesday, Health Canada's Baker said, declining to elaborate for privacy reasons. "The individuals in question are able to share it with you if they choose to," Baker said. Chopra declined comment and referred questions to his lawyer, who in turn referred calls to the scientists' union, the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada.

The union's president also declined to discuss the reasons given by Health Canada until a hearing is held, possibly in six months. "We will be addressing what Health Canada has put in the letters and we will be showing that, despite what they say, the real cause of the letters of termination is the public criticism of the department and the government of Canada," Steve Hindle said. "The fact that it's three (people fired) on the same day is unusual, and it also, I believe, lends credence to the argument we're putting forward that (the firings are) a result of them being whistle-blowers," Hindle said.

The firings outraged activist groups who said whistle-blowers need better laws to protect them. "All these scientists were trying to do was protect the food supply, and they got fired for doing their job," said Bradford Duplisea of the Canadian Health Coalition. The federal government had introduced new measures to protect bureaucrats who report concerns about their departments, but the proposed legislation was not enacted before the June 28 federal election.

Fired Scientists Spoke Out on Drug Approvals

By Paul Weinberg

Fromhealthcoalition.ca

The decision to fire three Health Canada veterinary scientists working in the government office that tests new drugs used on animals raised for food was made at the highest levels of the Canadian bureaucracy with the co-operation of the food and pharmaceutical industries.

That blunt statement comes from Michael McBane, co-ordinator of the Ottawa-based Canadian Health Coalition, which represents groups of seniors, farmers, women, labour unions and healthcare professionals. "The animal drug industry basically worked really hard with senior management in Health Canada and with the Privy Council office (which advises senior government leaders and helps set departments' policies), to have the scientists removed," McBane told IPS in an interview.

Adding to the controversy was the timing of the firings of Shiv Chopra, Margaret Haydon and Gerard Lambert --Jul. 14, just weeks after the national election and before a new group of ministers overseeing all departments, including Health Canada, were sworn in. At the time the three scientists in the department's veterinary drugs directorate were on stress leave after alleging harassment by departmental officials.

Health Canada spokesperson Ryan Baker declined to comment on the suggestion that officials and corporate powers colluded to orchestrate the firings, and called the dismissals "a personal matter." But Chopra told IPS his letter of termination cited "disobedience" as the reason for the action. "Given your previous disciplinary record and your continued unwillingness to accept responsibility for work assigned to you, I have determined that the bond of trust that is essential to productive employer employee relationship has been irreparably breached," Deputy Health Minister Ian Green wrote in the letter, reported The Canadian Press on Wednesday.

Steve Hindle, the president of the labour union that represents the scientists, says Health Canada "just reached the end of its rope" after years of reprimanding and suspending the scientists for their public opposition to the approval of specific veterinary drugs.

For example, resistance from Chopra, Haydon and Lambert towards a bovine growth hormone developed by agri-business giant Monsanto ultimately led to a Senate inquiry in the 1990s and a decision to not approve the drug in Canada. Also, before the May 2003 discovery of mad cow disease in a cattle herd in western Alberta province, which led countries like the United States and Japan to ban Canadian beef, Chopra and Haydon had warned that too little was being done by the food industry and its regulators in the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to prevent remains of dead cattle being used as feed for other cows. The Indian-born Chopra, who has successfully launched anti-discrimination cases against Health Canada for failing to promote employees of non-European origin, has no explanation for the timing of the firings, but says the loss in income is creating "new stress" for the researchers and their families.

Because they were dismissed from their jobs, they are not eligible for severance payments, he notes. Hindle's Professional Institute of the Public Service says it will appeal the firings before the Public Service StaffRelations Board, an independent tribunal that adjudicates disputes between the federal government and its employees, if Health Canada fails to reinstate them. Although Chopra applauds the union's support, he says the grievance appeal process will only deal with the technical and legal aspects of the department's action.

Left out, he adds, will be the substance of the issue: the ability of the powerful food and pharmaceutical lobbies to pressure Ottawa to bypass scientific concerns about the introduction of suspected cancer-causing hormones and the excessive use of antibiotics in animals; the latter has been singled out for the declining effectiveness of antibiotics on human beings. "The pharmaceutical companies openly for years kept on going to the Privy Council (and saying) that there are problems within veterinary drugs at Health Canada; they have backlogs of drugs that are not being passed. When we ask (the drug companies) for data, they don't produce any," Chopra adds.

But Jean Szkotnicki, president of the Canadian Animal Health Institute, the veterinary drugs industry association, denies her organisation played a role in the firings. In fact, her industry benefits from a "robust" review of animal drugs, she told IPS. At the same time, added Szkotnicki, Canada is losing potential research and development investment dollars from food and pharmaceutical companies because of the slow pace of testing of veterinary drugs at Health Canada.

The same drugs have been endorsed by officials in other countries after going through "a similar type risk assessment and risk management programme," she added. "We are often one of the last countries in the world to approve a product," according to Szkotnicki. Chopra counters that the animal drug industry has not produced any new products for many years, beyond "spreading and maintaining" the same types of hormones and antibiotics "of questionable safety" in the Canadian meat industry. McBane adds that the European Union (EU) continues to ban imports of Canadian beef because of its hormone content.

The issue is the right of government scientists to do their job, he adds. "At the end of the day, these scientists were performing their statutory duty under the law, in this case the Food and Drugs Act. And their senior managers, the deputy minister, the associate deputy minister and the director general were basically telling them to operate outside of the rule of law, to ignore the laws of Canada, and to expose Canadians to known health risks." Chopra says he expects the Senate to investigate the firings. In 1998 the standing Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry promised Health Canada scientists that in exchange for testimony on the safety of Canada's food, their jobs would not be jeopardised. "They told us, 'anytime, if anything happens to you, come to us'," recalls Chopra.

Scientist gets congratulatory letter from Health Canada after being fired

BY DENNIS BUECKERTOTTAWA

From healthcoalition.ca

Three weeks after firing Shiv Chopra for insubordination, Health Canada has sent him a gold watch and congratulatory letter praising his 35 years of "dedicated service." Chopra, one of three Health Canada whistleblowers fired on July 14, said he was insulted to get the glowing letter of praise after months of what he calls harassment by the department, culminating in his firing.

"Your years of service have not gone unnoticed and you have earned. . . praise and respect," says the letter signed by Deputy Health Minister Ian Green. "Please accept this special tribute as we honour you and your career. It's an acknowledgement of our sincere appreciation."

In contrast, Green's July 14 letter of dismissal cited concerns about Chopra's work performance and blasted him for "total lack of progress" in a project he had been assigned. "I have concluded that you have chosen to deliberately refuse to comply with my instructions," Green says in the earlier letter. "Given your previous disciplinary record and your continued unwillingness to accept responsibility for work assigned to you, I have determined that the bond of trust that is essential to productive employer employee relationship has been irreparably breached."

In the later letter, along with his gold watch Chopra received a framed, honorary certificate signed by Prime Minister Paul Martin. A Health department spokesman later said the award simply reflects departmental policy to recognize all veteran employees. "The reasons for Dr. Chopra's termination in July are not in any way related to his 35 years service award," Health Canada spokesman Ryan Baker said Wednesday. Chopra and his colleagues Margaret Haydon and Gerard Lambert, who were fired for insubordination on the same day, maintain they have been targeted because of their record as whistle-blowers. The scientists have said publicly they were being pressured to approve drugs despite human safety concerns.

In the late 1990s, they publicly opposed bovine growth hormone, a product that enhances milk production in cows. Their criticism led to a Senate inquiry and a decision not to approve the drug. During the anthrax scare following the September 2001 terror attacks, Chopra criticized then-health minister Allan Rock's decision to spend millions stockpiling antibiotics, saying the fear of bioterrorism was overblown. Chopra and Haydon warned last year that measures to prevent mad cow disease were inadequate. Subsequently a case of the disease was identified, with disastrous results for the beef industry. Health Canada has initiated numerous disciplinary proceedings against the scientists, who in turn filed grievances in a complicated tangle of cases, most of which they have won.

In a letter of grievance over his July 14 firing, Chopra says he was subject to "severe and debilitating harassment" over the 18 months preceding his dismissal. Chopra said that for five months this year, he was given no work to do.

He was then given a project but was separated from other colleagues with whom he needed to consult as part of his research. Chopra said that he, Haydon and Lambert were separated from other Health Canada employees and assigned to work in isolated offices where they had difficulty getting access to department data. All three say the stress of their battles at Health Canada have made them ill; a fourth member of the veterinary drug assessment group, Chris Bassude, died last year. ...Shiv Chopra, one of three whistleblowers who were abruptly axed last month, wasn't impressed with yesterday's home delivery.

"This is a very bad joke. This is adding insult to injury," he told Sun Media from his home in Manotick, outside Ottawa. "I completed 35 years of service on June 20, and on the 14th of July I got fired," Chopra said. "Now they send me this award for distinguished service." (Quotes from Sun Media)

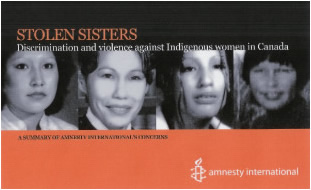

How many Sisters do we have to lose?

From Amnesty International Canada

Helen Betty Osborne was a 19-year-old Cree student from northern Manitoba. She dreamed of becoming a teacher. On November 12, 1971, four white men abducted her from the streets of The Pas. She was sexually assaulted and brutally murdered. A judge said later:

... the men who abducted Osborne believed that young Aboriginal women were objects with no human value beyond sexual gratification ... Betty Osborne would be alive today had she not been an Aboriginal woman.

The murder of Helen Betty Osborne – and her family’s long search for justice – is one of the nine stories of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls told in Stolen Sisters: Discrimination and Violence against Indigenous Women in Canada, a report by Amnesty International.

These stories represent just part of the terror and suffering that has been inflicted on Indigenous or Aboriginal women and their families across Canada.

This violence can be stopped. But only if Canadian officials take concerted action to protect the lives of First Nations, Inuit and Métis women and girls.

On March 25, 2003 – three decades after the murder of Helen Betty Osborne – her 16-year-old cousin, Felicia Solomon, went missing in Winnipeg. The first posters seeking information on her disappearance were distributed by her family, not the police. Parts of her body were found three months later.

Lives at risk

According to a Canadian government statistic, young Indigenous women are five times more likely than other women of the same age to die as the result of violence.

Indigenous women have long struggled to draw attention to violence within their own families and communities. Canadian police and public officials have also long been aware of a pattern of racist violence against Indigenous women in Canadian cities – but have done little to prevent it.

The pattern looks like this:

Racist and sexist stereotypes deny the dignity and worth of Indigenous women, encouraging some men to feel they can get away with acts of hatred against them.

Decades of government policy have impoverished and broken apart Indigenous families and communities, leaving many Indigenous women and girls extremely vulnerable to exploitation and attack.

Many police forces have failed to institute necessary measures – such as training, protocols and accountability mechanisms – to ensure that officers understand and respect the Indigenous communities they serve. Without such measures, police too often fail to do all they can to ensure the safety of Indigenous women and girls whose lives are in danger.

No excuse for government inaction

There is no excuse for government inaction. In fact, many of the steps needed to ensure the safety and well-being of Indigenous women have already been identified by government inquiries – including the inquiry into the murder of Helen Betty Osborne.

All levels of government should work closely with Indigenous women’s organizations to develop a comprehensive and coordinated programme of action to stop violence against Indigenous women. Immediate action should be taken to implement a number of long overdue reforms, including:

Institute measures to ensure that police thoroughly investigate all reports of missing women and girls

Provide adequate, stable funding to the frontline organizations that provide culturally-appropriate services such as shelter, support and counselling to help Indigenous women and girls escape from harm’s way

“When will the Canadian government finally recognize the real dangers faced by Indigenous women?” asks Darlene Osborne, a relative of Felicia Solomon and Helen Betty Osborne. “Families like mine all over Canada are wondering how many more sisters and daughters we have to lose before real government action is taken.”

The Human Rights of Indigenous Peoples: Overview

Despite some progress over the last decade, indigenous peoples around the world continue to live in hardship and danger due to the failure of states to uphold their fundamental human rights.

Indigenous peoples are being uprooted from their lands and communities as a consequence of discriminatory government policies, the impact of armed conflicts, and the actions of private economic interests.

Cut off from resources and traditions vital to their welfare and survival, many indigenous peoples are unable to fully enjoy such human rights as the right to food, the right to health, the right to housing, or cultural rights. Instead they face marginalisation, poverty, disease and violence – in some instances extinction as a people.

With the disruption of traditional ways of life, indigenous women may face particular challenges, losing status in their own society or finding that frustration and strife in the community is mirrored by violence in the household. For the growing numbers of indigenous women who have migrated to urban settings or who live on land with a heavy military presence, racial and sexual discrimination in the larger society may lead to a heightened risk of violence and unequal access to the protection of the justice system.

Promoting Global standards

Amnesty works with Indigenous peoples around the globe to advance urgently needed laws and standards to protect their cultures, livelihoods and territories. The most significant of these is the draft United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples [see right sidebar for link].

Denouncing abuses

Social marginalization and legal discrimination place Indigenous peoples at risk of a wide range of human rights violations directed against community leaders, individuals and Indigenous societies as a whole. Amnesty International takes action by exposing abuses in reports and the press, and by mobilizing public pressure through tools like our Urgent Action Network.

Holding Canadian officials responsible

The Canadian government has told the United Nations that the situation of Indigenous peoples is “the most pressing human rights issue facing Canadians.” Yet the Canadian government has repeatedly failed to implement UN the recommendations of UN human rights bodies concerning the protection of Indigenous peoples’ rights in Canada . Amnesty International’s work in Canada has included the land rights of the Lubicon Cree, the police shooting of Dudley George, and violence against Indigenous women.

"For far too long the hopes and aspirations of indigenous peoples have been ignored; their lands have been taken; their cultures denigrated or directly attacked; their languages and customs suppressed; their wisdom and traditional knowledge overlooked; and their sustainable ways of developing natural resources dismissed. Some have even faced the threat of extinction.... The answer to these grave threats must be to confront them without delay." -Kofi Annan, U.N. Secretary General 2004

Mos Def Arrested After Performing 'Katrina Klap' Outside Awards Show

From GNN

2006

Mos Def was taken into custody and charged with disorderly conduct Thursday night after an unauthorized performance outside Radio City Music Hall during the Video Music Awards, police confirmed to MTV News. He was released early Friday (September 1) morning.

According to authorities, the rapper pulled up in front of the venue in a flatbed truck at around 10 p.m. for an impromptu show for the people gathered outside. An NYPD spokesperson said officers asked Mos Def and members of his entourage to shut down their operation due to crowd conditions and the overall safety of everyone involved.

It wasn’t clear whether Mos Def (real name: Dante Smith) ignored or refused the orders, the police spokesperson continued.

Sources close to the rapper said Mos Def was performing “Katrina Clap,” a freestyle indictment of the Bush administration’s slow response to last year’s hurricane victims in New Orleans.

After Mos Def arrived at Radio City Music Hall with his team in tow, the source said, officers on the scene approached the truck inquiring about a permit. When police were told a permit was in possession, officers let the one-song performance continue.

The source said additional officers then approached the rapper demanding the operation be shut down immediately. The order wasn’t communicated to Mos Def immediately, so the rapper didn’t end his performance right away, the source said. Police then began to arrest members of the rapper’s entourage, including his brother, according to the source. According to a statement released by Mos Def’s publicist on Friday, the rapper did not have a permit.

“Mos Def chose to use his voice to speak for those who are losing their own during this critical period of reconstruction,” the statement reads. ”[He] was in the middle of performing and as soon as he was made aware of the police’s presence, he shut everything down.

His staff and team were willing to comply as well but the police overreacted. Mos Def was not charged but given a summons for operating a sound-reproduction device without a permit, which he is going to contest.”

Members of Mos Def’s camp say they videotaped the incident and will publish it, possibly on a Web site, to shed light on their side of the confrontation.

The Development of Postmodernism

Wikipedia

(excerpt)

From modernism

Modernity, is defined as a period or condition loosely identified with the Industrial Revolution, or the Enlightenment. One "project" of modernity is said to have been the fostering of progress, which was thought to be achievable by incorporating principles of rationality and hierarchy into aspects of public and artistic life. (see also post-industrial, Information Age). Although useful distinctions can be drawn between the modernist and postmodernist eras, this does not erase the many continuities present between them. One of the most significant differences between modernism and postmodernism is the concern for universality or totality. While modernist artists aimed to capture universality or totality in some sense, postmodernists have rejected these ambitions as "metanarratives."

This usage is ascribed to the philosophers Jean-François Lyotard and Jean Baudrillard. Lyotard understood modernity as a cultural condition characterized by constant change in the pursuit of progress, and postmodernity to represent the culmination of this process, where constant change has become a status quo and the notion of progress, obsolete. Following Ludwig Wittgenstein's critique of the possibility of absolute and total knowledge, Lyotard also further argued that the various "master-narratives" of progress, such as positivist science, Marxism, and Structuralism, were defunct as a method of achieving progress. Writers such as John Ralston Saul among others have argued that postmodernism represents an accumulated disillusionment with the promises of the Enlightenment project and its progress of science, so central to modern thinking.

Notable contributors