Challenging Impunity

The International Criminal Court was launched in April 2002. Noah Novogrodsky outlines the goals of the Court and describes the barriers to its success.

From New Internationalist

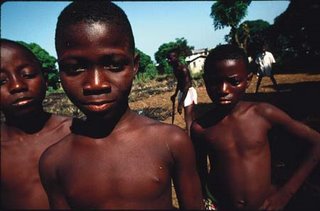

In mid-October this year the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued indictments for the arrest of Joseph Kony and four other leaders of Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The LRA is notorious for a 21-year campaign of terror in Northern Uganda – including the abduction of thousands of children and the widespread use of child soldiers. Kony and the other LRA leaders are charged with ‘crimes against humanity’ and ‘war crimes’.

The case against the LRA is a test of the power and limits of the ICC just three years after its birth. The new legal body taking shape at The Hague is a direct legacy of the Nuremberg tribunals which tried Nazi war criminals after World War Two. But unlike Nuremberg the ICC contains the promise of a universal court for universal crimes.

It is this elusive goal that sustains the victims of human rights abuses hungry for individual accountability, the diplomats who negotiated the Court’s creation in Rome during the summer of 1998, and the international lawyers and activists who desperately want such an institution.

Supporters of the Court believe it is the most significant advance in international human rights law in the last half-century. In addition to Northern Uganda, the ICC has begun investigations into atrocities in the Congo and, most recently, in Darfur, Sudan. The Chief Prosecutor, Luis Moreno-Ocampo, is an Argentinean with a domestic record of successful prosecutions of corrupt politicians, organized criminals and the generals responsible for mass ‘disappearances’ during Argentina’s ‘dirty war’ of the 1970s and early 1980s.

Naming war criminals

But what can the Court really do? The ICC has no police force connected to its operations, so it can’t directly arrest indicted suspects. If the prosecutor can persuade UN peacekeepers or sympathetic states to arrest suspects, the Court will provide criminal justice for a select number of the world’s worst killers. In the process the ICC hopes to destigmatize warring communities and rid them of collective guilt by assigning blame to individuals.

For victims and their families the Court offers the possibility of retribution through law – a forum where they can bear witness to the atrocities they’ve experienced – and a compensation fund. Equally important, the ICC aims to influence international politics by naming and isolating war criminals. In 1999 Louise Arbour, former UN war crimes prosecutor for the Balkans, timed the indictment of Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic to ensure that NATO would not cut a deal over Kosovo with a criminal suspect. Two years later, Milosevic was arrested by Serbian police and turned over to the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.

Even without its enforcement problems, the Court will have to overcome external enemies and internal deficiencies. The fact that the ICC’s first cases are all in Africa has led to the predictable charge that the Court represents the selective imposition of Western values on poor states.

The Court is an international anomaly – an institution created by treaty among 99 states that functions without the co-operation of a few key actors, many of whom are openly hostile to it. That treaty – the 1998 Rome Statute – is the product of compromise. In the end, the Treaty created a court capable of prosecuting only three universal offences: war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity.

The result is a codification of international criminal norms which will stop the creation of ad hoc UN criminal tribunals – like the ones for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. The Court’s statute identifies rape and torture as crimes against humanity and provides clear definitions of liability for officers in command positions who are barred from arguing that they were simply ‘following orders’. The statute also guarantees defendants substantial ‘due process’ protections (for the accused) and preserves a right of appeal. Despotic heads of state from signatory states are stripped of the immunity that allowed Idi Amin, Uganda’s one-time dictator, to retire in luxury. The Court also entrenches the principle of ‘complementarity’ – which means the ICC will step aside if legitimate national courts decide to try war criminals.

The ICC has the power to investigate human rights abuses on the territory of states that have signed and ratified the treaty or when the suspect hails from a signatory state. If the Security Council refers a matter to the Court, as it did belatedly in response to the slaughter in Darfur, the ICC may take jurisdiction even where the affected state objects to the presence of outside investigators. But more often cases will come from a state that is unable or unwilling to prosecute serious crimes committed on its own soil. In Uganda, for example, the Government is all too willing to let the ICC prosecute the LRA. (If the Court were to indict Government soldiers for their abuses, the picture might look very different). Any mass crime, committed in a signatory state unable to mount a genuine prosecution, can come before the ICC.

Of course, the Court only binds those states (and, by extension, individuals from those states) that sign and ratify the treaty. In theory, however, the Court could exercise jurisdiction over an individual from a non-state party who commits grave violations on the territory of a signatory state. Peacekeepers or foreign forces from non-state parties are potentially bound to the Court if they are arrested for crimes committed on the soil of a signatory state.

Bilateral deals

This is the source of the United States’ well-publicized opposition to the Court. Notwithstanding a litany of safeguards – among them the ICC’s limited jurisdiction to try only the most egregious international crimes, the Court’s inability to try crimes committed on US soil and its explicit deference to domestic procedures – the Bush Administration so loathes the ICC that it attempted to ‘unsign’ the treaty. (President Clinton actually signed the treaty on 31 December 2000 but refused to submit it to the Senate for ratification.)

Washington has not only refused to join the Court, it has actively lobbied against it. In response to concerns that the Court would try US soldiers or officials in frivolous or politically motivated cases, the Bush Administration has negotiated bilateral deals with dozens of countries who’ve agreed never to surrender US citizens to the Court, regardless of the alleged crimes or the site of the offence. Congress also passed the ‘American Servicemembers’ Protection Act’ which prevents the US from aiding the Court. The bill was nicknamed ‘the Hague Invasion Act’ – the ICC is based in the Netherlands and the act pre-authorizes the President to use force to free American soldiers or their colleagues if they were ever brought before the Court.

External opposition is not the Court’s only problem. The limited scope of the ICC’s statute precludes it from seizing jurisdiction over many high-profile international crimes. For example, although the ICC was created by the UN, attacks on UN personnel may only be considered if committed during an armed conflict on the territory of a member state. When the UN’s headquarters in Baghdad was blown up in the summer of 2003, ICC investigators were powerless to probe the incident.

The Court’s focus on consensus definitions of war crimes and genocide limits its range of potential cases and leaves it, quite literally, fighting the last war. The ICC thus reflects the tragedy of Bosnia in 1993, not Afghanistan in 2005. Post 9/11, suspected non-state terrorists are detained by US forces in legal limbo at Guantánamo Bay. And human smugglers operate unchecked in states with underdeveloped legal systems, instead of being sent to the ICC.

Finally, the ICC faces the very real problem that it is powerless to address abuses arising from many of the world’s great powers. Russia, China, Iraq, India, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia and Indonesia have joined the US in refusing to sign the Rome Treaty. Much of this is due to domestic concerns – Iran has no interest in allowing an international body to examine the horrors of Iranian prisons. But the cost to the international community is significant. China and India are burgeoning economic and geopolitical powers; their absence from a court capable of trying individuals according to common standards erodes the notion of universal justice. At present, sex traffickers, arms dealers, even international terrorists, from countries that have not signed the Rome Statute, are beyond the Court’s reach.

The ICC is left to prosecute ‘crimes against humanity’, ‘genocide’ and ‘war crimes’ in states that have joined the Court. In addition to Uganda, the list of signatories where such crimes may have been committed since 1 July 2002 includes the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia, Colombia and Sierra Leone. Civil wars may explain why each of those states has joined – they are undoubtedly hoping the Court will prosecute rebel forces – but the legal hook remains. Sadly, there is little current evidence that the spectre of ICC prosecutions has changed the behaviour of human rights abusers on the ground. In Northern Uganda many human rights advocates fear that the ICC will complicate efforts to achieve a negotiated settlement after decades of fighting.

The challenge will be to conduct fair and transparent trials in the face of criticism that the Court is merely a vehicle for Northern states to condemn select crimes in the South – not an instrument of universal justice. Over time the states that have joined the ICC hope to persuade the others. The goal is to lead by example, prosecuting humanity’s worst crimes effectively and reversing the past century’s culture of impunity.

Continued US opposition hurts but, as the Uganda indictments demonstrate, the Bush Administration has been unable to derail the ICC. Likewise, a change in the US position will not guarantee the Court’s future success. For that, its fortunes may well turn on an expansion in the list of crimes within its authority and the involvement of emerging powers as members.

Imagine this: an institution that includes China and India – and can prosecute Joseph Kony as well as Private Lynndie England of Abu Ghraib infamy. That will truly be an International Criminal Court.

The ICC has just targeted Uganda’s Lord’s Resistance Army for crimes against humanity, including the abduction of children as armed fighters. These former child soldiers are now at a rehabilitation centre in neighbouring Sierra Leone. Photo: Clive Shirley / Globalaware

Noah Benjamin Novogrodsky is Director of the International Human Rights Program and Adjunct Professor of Law at the University of Toronto

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home